It was a cold winter morning. Alex woke up, pulled on her socks, gathered her cosy little blanket, and ran downstairs to the living room. She found her father poking at the fireplace with an iron rod to get the fire burning comfortably. Once done, her father settled down on the couch near the fireplace, reading his morning newspaper.

“This feels so good. Isn’t fire the best thing ever?” Alex said, rubbing her palms together in front of the fireplace to make them warm.

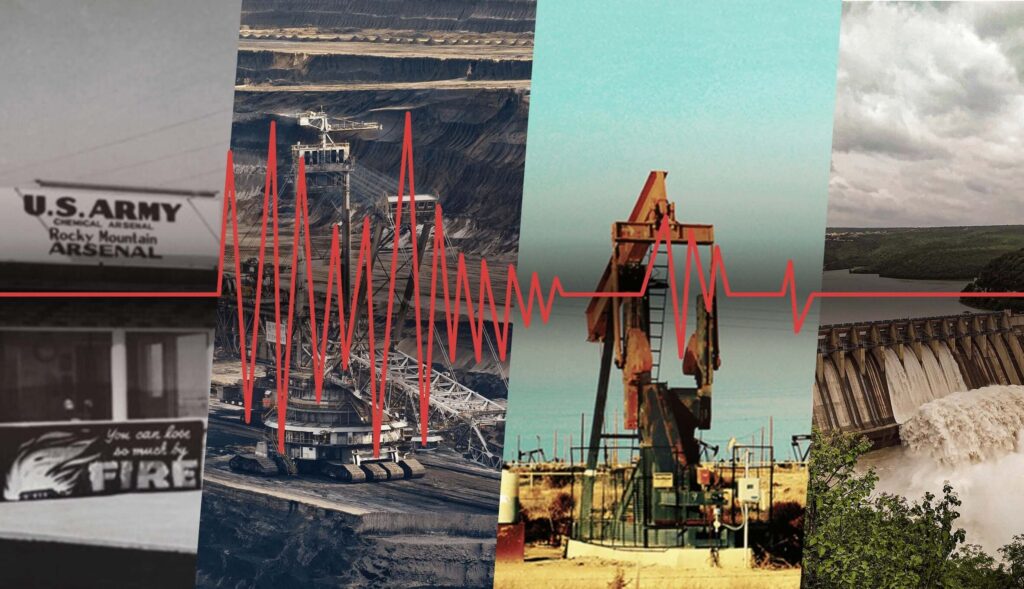

Her father sighed and read a headline from the newspaper. “A fresh wildfire in northern California spread rapidly on Thursday, burning homes and prompting evacuation orders in a rural community.” “Isn’t fire the worst thing ever?” he asked.

Alex was perplexed but curious. Being able to make fire in the fireplace was a luxury. How could the same thing cause the devastation of wildlife and rural homes? How could the smoke and fumes from the bushfires destroy the air quality so badly?

What is fire? How do we get fire? How can fire be so useful and destructive at the same time? When was it first discovered? All these questions raced through Alex’s mind.

A Spark in Time: When Was Fire Discovered?

“Wait. Too many questions. Let’s answer them one at a time,” said her father. He folded the newspaper and said, “Alright, let’s start from about 1.5 – 2 million years ago.”

“Imagine you are living in the era when our ancestors strolled on Earth. Homo erectus, in particular. They are said to be the longest-surviving species of humans to date, even longer than us – the Homo sapiens. You are merely part of a hunter-gatherer family. Your life’s purpose is to find food on a daily basis to survive. Berries, vegetables, nuts, insects, and small animals are your food. And you eat it all just as you find it – raw.

And then one day, the forest you live in is swarmed with an orange wave, and the sky is filled with smoke. You had heard about this scary orange miracle before but never witnessed it yourself. You find animals along the way, all charred to brown and black. You run for your life, trying not to end up like them.”

Image: A forest fire, Image source: unsplash.com

From Fear to Tool: Humanity’s Relationship with Fire

“You reach the mountaintop and watch the forest covered in smoke and orange flares. Your brother comes around with a burnt (roasted in the forest fire) dead rabbit he picked up on the way.

Your eyes light up in delight as you take the first bite of the roasted rabbit. You have never tasted such tasty meat before. It is soft, juicy, and delicious. From that day on, you wait for the forest fires. The hunt for roasted animals begins. The desperation to tame this miraculous force of nature also grows with each passing day.

It starts by chasing bushfires and lightning strikes. You learn how to store the warm, flickering embers in a twig or a thick, smoldering branch. This was the first step towards the controlled use of fire, allowing you to carry it back to your abode to make more of it out of dry leaves.”

Mastering the Spark: How Was Fire First Made?

“So, when did we learn to create fire on our own?” Alex asked her father.

He replied, “One fine morning, you are playing with stones with your brother. You throw one towards him, and it hits another stone. Instantly, it produces a golden flare that lasts for just a moment.

You both get curious. You start striking stones together to produce the golden spark again. In one out of ten times, you are able to produce a spark! Especially when you hit it so that the contact surface is minimal and the rate of strike is fast.

You keep trying relentlessly over a bunch of dry leaves and twigs. And then one day, the spark creates that yellowish-orange hot thing – FIRE! You have finally found a way to create it on your own. That must have been the most remarkable day in the history of mankind. Harnessing fire has helped humans survive and evolve on Earth for over a million years,” said Alex’s father.

The Science of a Flame: What is the State of Matter of Fire?

“So, is fire a solid, liquid or gas?” continued Alex.

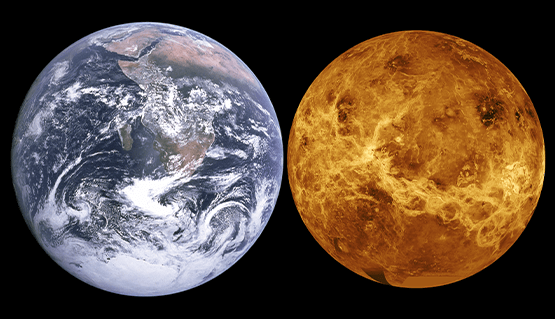

“That’s a great question. Fire is a fascinating chemical process, and its state of matter isn’t simple. It’s often considered plasma, which is an ionized gas at high temperatures. An ‘ion’ is an atom with an unequal number of electrons and protons. In an ionized gas, some electrons become completely free from their atoms, resulting in a mix of ions and free electrons. However, in some cases, like a simple candle flame, the fire is just a mixture of hot gases and not plasma.

Interestingly, plasma is what makes up some of the hottest fires in the universe. In fact, all stars, including our Sun, are burning balls of plasma. It’s also the most abundant state of matter found in space,” answered Alex’s father.

The Fire Triangle: What You Need to Make Fire

“So, what are the key ingredients for fire?” Alex asked eagerly. Her father was happy to see her getting curious.

“To understand how to make fire,” he said, “you need to know about the fire triangle. It’s the simple recipe for fire. You need three basic things:

- Fuel to burn (like wood, gas, or paper)

- Oxygen from the air

- Heat to start the process

These three elements – Heat, Fuel, and Oxygen – form the fire triangle. If you remove any one of them, the fire goes out. The heat is the energy needed to start the chemistry of fire, which is a rapid chemical reaction called combustion.

In the case of a lighter, you’re creating fire using an electric spark (Heat) that ignites the combustible gas (Fuel). Oxygen is readily available in the air around it.”

As Alex listened keenly, her father lit a candle. He brought it close and asked her, “What do you find interesting in the flame of the candle?”

“Its shape and colours,” replied Alex without hesitation.

Anatomy of a Flame: Colors and Temperatures

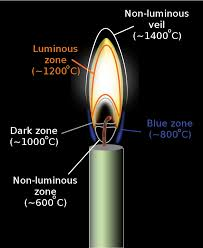

“Exactly!” her father explained. “A flame is the visible, gaseous part of a fire. The color changes from the innermost to the outermost part. Unsurprisingly, the temperature also varies within the flame itself. The outermost part of the flame is almost invisible and is the hottest. The innermost part has the lowest temperature and is also non-luminous.

Between those, the dark zone (~1000°C), the blue zone (~800°C), and the bright yellow luminous zone (~1200°C) make up the other zones of temperature within a candle flame.”

Image: Various zones of a candle flame Image source: wikipedia.com

Why Is a Flame Teardrop-Shaped?

Alex observed, “Why is the flame teardrop-shaped?”

Her father explained further. “When a candle burns, it heats the air around it. Hot air is less dense, so it starts to rise. As the hot air moves up, the surrounding cooler, heavier air rushes in to replace it at the bottom of the flame. This continual cycle of upward-moving air, driven by gravity, gives the flame its classic teardrop shape.

Can you guess what happens to the shape of a flame on the International Space Station? In microgravity, there’s no ‘up’ for the hot air to rise to, so flames become almost spherical! You end up with circular balls of fire.”

“Fascinating,” said Alex.

Suddenly, the fire alarm started blaring. Alex and her father rushed to the kitchen to find a dish towel had caught fire on the stove. Alex’s father grabbed the small red cylinder from under the sink, pulled the pin, and sprayed a thick foam all over the flame. The fire died within a few seconds.

Alex was now more intrigued than ever. She read the label on the cylinder: Fire Extinguisher. Her next question was obvious.

Fighting Fire with Science: What Is a Fire Extinguisher?

Her father explained, “Remember the fire triangle? A fire extinguisher works by removing one of its sides. For instance, when we sprayed the foam, it smothered the fire, cutting off its supply of oxygen and breaking the triangle.

That’s why things that cut off oxygen are effective fire extinguishers. You may have seen buckets of sand or water kept in buildings for emergencies. When poured on a fire, they block its contact with the air.

In fact, there are different types of fire extinguishers for different types of fire.” He pointed to the list on the side of the cylinder. “These are the main classes:

- Water: For combustible solids like wood, paper, and fabric.

- Foam: For combustible solids and flammable liquids.

- Dry Powder: A versatile extinguisher for solids, liquids, and flammable gases.

- Carbon Dioxide (CO2): Best for flammable liquids and electrical fires.

- Wet Chemical: Specially designed for cooking oil and fat fires, like the one we just had.”

Image: A fire extinguisher extinguishing fire, Image source: compli.com

“Now I get it,” exclaimed Alex.

“Perfect. Now let’s get back to the living room. It’s cold, and we need some fire,” laughed her father.

“Ironic, isn’t it? The very thing that is a necessity for us can become a nightmare if it goes out of control. Knowing how to control fire spawned new cultures, fueled the social growth of human beings, and helped us survive and evolve. Yet, we still struggle to contain it when it rages out of our control. Nature, after all, is the most powerful force.”

With that, Alex’s father went back to reading his newspaper, and Alex went off to look for food – breakfast!

Read More :

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4874402/

- https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article-abstract/59/7/593/334816

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0379711281900369

Footnote: The study of fire is a cornerstone of scientific research. The research methodology for understanding it combines both qualitative research (observing a flame’s color and shape) and quantitative research (measuring its temperature). For any young scholar, this topic makes an excellent science fair project, bridging simple experiments with fundamental STEM principles. Deeper analysis of combustion is frequently covered in top international journals and other scholarly sources, highlighting its importance in science and tech.